|

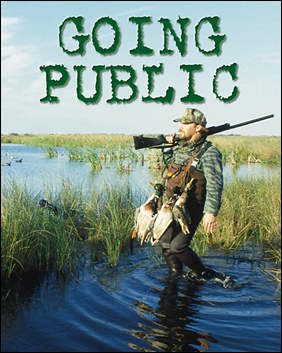

Public waterfowl hunting along

the Upper Texas Coast is remarkably affordable, and-provided you

have the right gear-remarkably productive. Public waterfowl hunting along

the Upper Texas Coast is remarkably affordable, and-provided you

have the right gear-remarkably productive.

By Shannon Tompkins

They came in waves and clouds

and clumps, swarming from every direction in the pink and blue

dawn sky.

The opening in our decoy spread

transformed into something very much like Houston Intercontinental's

main runway on Thanksgiving week. While one bunch of ducks swept

low over the marsh pond to settle on the brackish water between

the blocks, other groups swung downwind, lining up for their approach

and landing. At times there were three or four flocks of birds

vying for air space over the six dozen or so decoys.

A constant stream of ducks-teal,

pintail, mottled ducks, gadwall by the heaps, wigeon, shovelers

and ringnecks sailed on stiff wings and floated down from the

sky. The air reverberated with quacks, whistles, peeps, purrs

and the sound of feathers cutting wind.

For about the first 10 minutes

of shooting time, we just sat in our cordgrass hides and never

fired a shot. Not a word passed between the three of us. We just

took it in, mesmerized.

A thin, reedy "rrrreeekk"

broke the spell.

There. That bunch to the east!

Big, blocky ducks-a dozen or so.

Mallards! A greenhead's

distinctive call gave them away. The birds came on, spotted the

decoys, swung north of the pond, turned into the slight south

wind and locked their wings.

My grip on the old pumpgun

tightened. I could feel my two brothers-Les and Rick-tensing,

too, even though they were hidden from view in clumps of wiry

cordgrass.

When the mallards hovered over

the landing zone, at the exact moment when they hung still in

the air and were most vulnerable, the unspoken communication that

comes from hunting together for more than a quarter-century took

over. At the telepathic command, the three of us rose to our knees

and dropped a bird apiece.

At the shots, the dozens of

birds sitting in the decoys slapped their wings on the tea-colored

water and lifted off the pond. They milled and circled. Some drifted

back toward us. Others beat toward nearby ponds. Still other ducks

appeared on the horizon, headed our way.

"This is as good as it

ever could get," Rick said as he stood, shotgun in one hand,

greenhead in the other, and swiveled his head to see ducks in

every direction.

He said it more to himself

than to Les and me. But we heartily agreed. This was as good as

it gets-and it stayed that way through the morning as we traded

opportunities, picking big drake pintails, wigeon, fat gadwall

and mottled ducks one at a time until we'd filled our limits.

That opening morning just a

couple of seasons ago was one of the best in a 30-year love affair

with waterfowl hunting, one that has been filled with dozens of

such incredible mornings in the marsh.

Probably just as incredible,

to many, is that almost anyone could have duplicated our hunt

and all those others. All of them happened not on some exclusive

leased tract, or under the hand of some commercial waterfowl outfitter,

but on an open-to-anyone expanse of coastal marsh held and managed

for wildlife-particularly waterfowl-by federal and state wildlife

agencies.

Cost of access? Ten dollars

is the most a person has to spend to access any of the tens of

thousands of acres of premier waterfowl habitat contained in about

a dozen federal wildlife refuges and state wildlife management

areas along the upper half of the Texas coast. On many of these

areas, hunters pay no fee for accessing some of the best duck

hunting opportunities in the state.

In Texas, where about 97 percent

of the land is in private hands and access to the best hunting

for quail, deer, turkey and other game is available only to those

with the largest bank accounts, waterfowl hunting is an anomaly.

While public hunting opportunities for deer and other game are

minimal and the quality, in most cases, suspect, public waterfowl

hunting areas are abundant and provide a quality of hunting as

fine as on the most expensive and well-managed private tracts.

How good?

On opening day of the 1997

September teal-only hunting season, the first 40 hunters who checked

out of the Mad Island Wildlife Management Area near Matagorda

had their 4-teal limits.

On the Sargent Special Permit

Area of the San Bernard National Wildlife Refuge, hunters during

the first part of the 1997-98 regular duck season averaged more

than 4 birds per person.

On the 24,250-acre J.D. Murphree

WMA near Port Arthur, the 3,398 hunters who participated in duck

hunts during the 1997-98 season bagged an average of 2.8 ducks

per person. During the first of the 2-part duck season, hunters

averaged 3.32 ducks apiece.

On the McFaddin NWR near Sabine

Pass, hunters averaged better than three ducks a day.

Considering the public hunting

areas are open to all comers and attract waterfowlers of every

skill level-from first-timers to gray-bearded veterans of many

a marsh campaign-those averages are impressive and show the quality

of hunting available on the areas.

But it's the quality of the

habitat on those public areas that make them such duck magnets.

And ducks are what they attract, mostly. Geese do use the areas,

sometimes in abundance. But ducks are the big draw.

The majority of the habitat

contained in the national wildlife refuges and state wildlife

management areas along the coast is brackish marsh. Some areas

hold salt marsh. Others hold a bit of freshwater marsh.

Oh, there's coastal prairie

on some of the areas, and even some crop land-rice, mostly. But

it's the marsh that makes the places so attractive to tens of

thousands of wintering waterfowl.

The dozen-plus tracts of public

hunting lands on federal refuges and state wildlife management

areas along the upper coast, from Sabine Pass to the mouth of

the Guadalupe River, have been the destination of migrating waterfowl

since the most recent ice age ended about 10,000 years ago. And

the ponds and sloughs and shallow open lakes dotting the coastal

marshes attract ducks by the thousands.

Hunters have been coming to

those marshes to pursue the birds for almost that long. But for

most of this century, the marshes now opened for public hunting

were the purview of the landed elite or those monied enough to

pay for leasing prime tracts.

With the exception of the J.D.

Murphree WMA near Port Arthur, which the old Texas Game, Fish

and Oyster Commission bought in the 1950s and began a public

waterfowl hunting program late in that decade, all of the coastal

areas now open to public hunting were in private hands barely

a couple of decades ago.

Most of the dozen or so tracts

were sold to federal or state agencies and opened to the public

within the past 20 years, and some have been incorporated into

the refuge or WMA programs within the past five years. (The Middleton

Tract of the Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge, for example, was

opened to public hunting just two seasons ago.)

Today, these tens of thousands

of acres of what were premier private waterfowl hunting areas

are now available to anyone, often at no charge and again, never

at more than $10 per day.

Some are open to waterfowl

hunting every day of the season. Others are open just a couple

of days a week, with the limited pressure ensuring high-quality

hunting. Some have walk-in access. Others require a lengthy boat

ride. All can produce world-class duck hunting.

But that high-quality hunting

doesn't just happen. Truth is, many hunters who visit public waterfowl

hunting areas come away disappointed.

continued

page 1 / page 2

|